Collective rights

Most human rights treaties and covenants protect individual rights, and only a few protect collective rights. Among the latter are the UN instruments that protect languages and cultures, ensure the right to association and religion, and—notably—the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Collective rights are rights held by a community, a people or a group rather than single individuals. They should not be confused with the rights held by the members of a certain category of individuals and not by the rest of humankind (such as woman rights, which are held by women severally, not women as a group). Collective rights are both overlapping and interdependent with the individual rights of the single members of a group, such as an indigenous people, not as an alternative to them.

Some confusion may arise over which groups are or should be entitled to be holders of collective rights. Not all groups of people (e.g., those attending a concert or those with green eyes) may be considered to have a value worth of legal protection through the instrument of rights. Collective rights are, in fact, justified on the protection of the group per se because it is perceived to have intrinsic value. Indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities are the groups most commonly argued to be holders of collective rights.[1] On the one hand, their collective rights stem from their capacity to hold, maintain and let flourish cultural diversity in society. On the other, they often find themselves in particularly vulnerable positions. The “effective realization of equality requires in many instances differential treatment of ethnic groups in ways not necessary for, or even relevant to, other types of groups”.[2]

For what concerns the ICCA Consortium, among the most interesting collective rights are the customary and/or legal tenure rights to a territory, implying access, use, management and the power of excluding others (see #Tenure and security of tenure).

Are local communities holders of collective rights?

Indigenous peoples are now widely considered by international law and several national laws as holding intrinsic value collectively (not only as an aggregation of single members). In contrast, local communities are still struggling to see their collective rights recognized. Local communities, it is at times argued, are not per se holders of intrinsic value, hence they do not have collective rights per se. The debate on the recognition of rights to local communities has currently reached the stage of recognizing local communities as holders of collective rights only insofar as their lifestyles contribute to achieve internationally agreed values, such as conserving biodiversity or securing the right to life, food or culture. An important step towards such increased recognition is the adoption by the UN General Assembly of the Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP). Acknowledging their role for food security and sovereignty, UNDROP aims at promoting specific collective ways of life, as well as their contribution to conserving biodiversity.

The ICCA Consortium is keen to understand and highlight all the instances by which local communities could argue for their collective rights to territory on the basis of customary tenure as well as contributions to broadly agreed international values, such as the conservation of biodiversity, but also the right to life, food[3] or the preservation of cultural diversity.

What is a ‘person’?

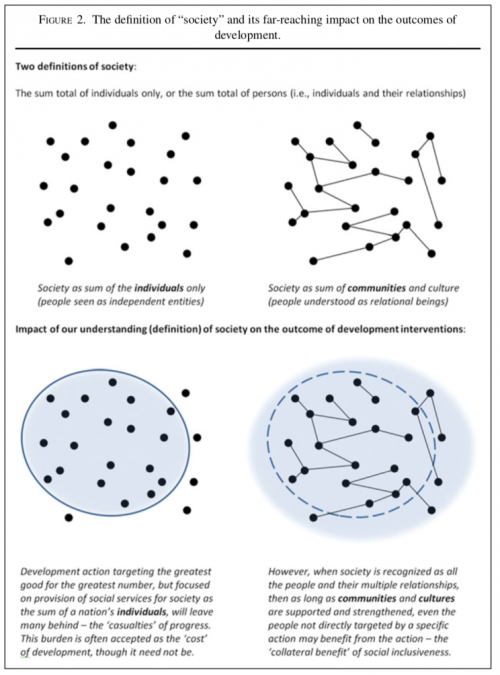

What makes or constitutes a ‘person’, or an ‘individual’, is not as straightforward as one might think. Western predominant view has considered, and entrenched into law, the fact that individuals are biophysical beings detached from one other. It has focused on their single isolated concerns, needs, rights and duties.

Non-Western cultures and worldviews have often reflected a wider and less mono-centred view of ‘person’. As expressed by Torrance:[4] “Just as the words ‘father’, ‘mother’, ‘husband’, ‘wife’, ‘brother’, ‘sister’ are relational terms, so could be the word ‘person’.” In this sense a person would be “someone who finds his or her true being in relation, in love, in communion [with others]”. If ‘persons’ are perceived in a symbiotic relationship with one another and the world at large, there are profound implications for what society is and what social wellbeing implies.[5] For instance, this symbiotic vision would much more easily conceive territorial rights and responsibility as residing in custodian communities rather than individual landowners.

Key references:

Torrance, 1996; Anaya, 1997; Holder and Corntassel, 2002; Waldron, 2002; Stevens, 2010; Jonas, Makagon and Shrumm, 2013; Foggin, 2014; Reyes, 2017.

For more info on the collective rights of indigenous peoples see UNDRIP and for the Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas, see: La Via Campesina

[1] Some indigenous peoples are vehemently opposed to being referred in any way as ‘ethnic minorities’.

[2] Anaya, 1997, page 223.

[3] Pimbert and Borrini-Feyerabend, 2019.

[4] Torrance, 1996.

[5] From Foggin, 2014.