Conserved areas

In an intuitive sense, ‘conserved areas’ are territories or areas that achieve conservation de facto. They were defined in 2015 as areas that “regardless of recognition and dedication, and at times even regardless of explicit and conscious management practices, achieve conservation de facto and/or are in a positive conservation trend and likely to maintain this trend in the long term”.[1] In this sense, conserved areas are clearly not one and the same with protected areas, but they have overlaps, e.g. wherever a protected area manages to achieve its conservation objectives. In some cases, however, protected areas do not achieve their conservation mission – i.e. they are protected but not conserved. In other cases, however, areas that are not listed as protected do achieve conservation. Many ICCAs—territories if life are examples of the latter situation: they conserve nature de facto, as part of biocultural systems, without being listed in an official protected areas system (other ICCAs are included in the protected areas system, with or without the consent of the original custodians).

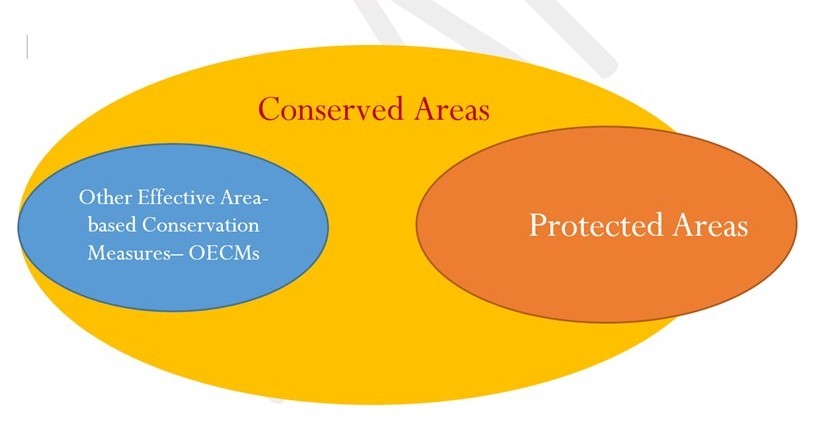

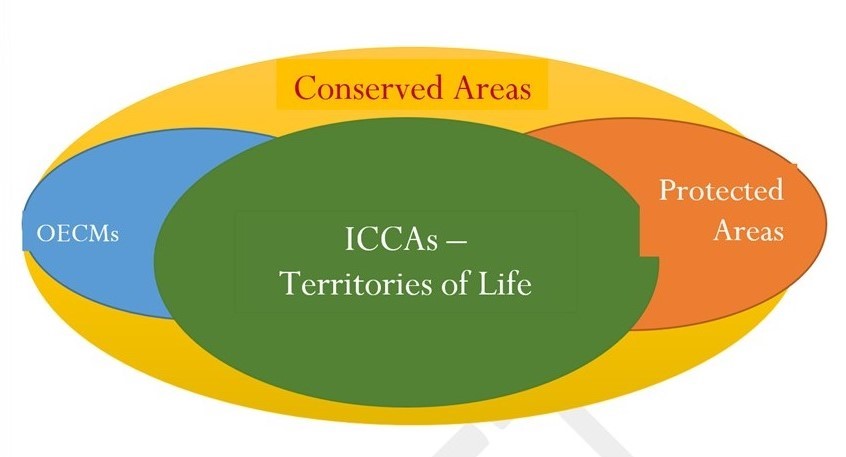

Since 2010, the Convention on Biological Diversity has used the term ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs), which are defined as “geographically defined areas other than protected areas, which are governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and, where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio–economic, and other locally relevant values”.[2] ‘Conserved areas’ should not be used as synonymous for OECMs for more than one reason. As conservation happens also in areas that are not at all governed or managed, the overlap cannot be complete. But conservation also happens in protected areas, and OECMs are defined as being entirely separate from protected areas. Thus, equating OECMs with ‘conserved areas’ would have the paradoxical consequence that the terms ‘protected’ and ‘conserved’ would be incompatible in CBD parlance. A more logical conceptual arrangement is shown in figure 3 and 4 below:

In Figure 4, ICCAs— territories of life are shown as fully overlapping with conserved areas but also with protected areas or OECMs. It is up to the community custodians of the specific territories of life to decide whether they wish to be recognised as protected areas, as OECMs or do not wish any such recognition and overlap. Conserved areas whose borders, governance institutions, and management practices are not recognised could be more vulnerable, but inappropriate recognition may be worse than no recognition at all. The ICCA Consortium strives for the appropriate recognition of ICCAs—territories of life at local, national and international levels, and for providing them with appropriate support (see #Appropriate recognition, #Appropriate support).

Despite the crucial role of conserved areas, their total extent on our planet is currently not known or monitored. The organisation dedicated to monitor global conservation (World Conservation Monitoring Centre of UN Environment, or WCMC) has focused for decades only on data about protected areas submitted by state governments[3] and only recently opened-up to listing various forms of governance of protected areas and OECMs. Interestingly, it accepts today data on ICCAs—territories of life and encourages directly submission by their community custodians. In association with the ICCA Consortium, WCMC has been recommending that community custodians organise their own peer-support and peer-review networks to provide data comparability and quality control (see #Networks focusing on ICCAs—territories of life).

Of major value for understanding both conserved areas and territories of life is the question of the extent of their overlap. In her pioneer analysis, Liz Alden Wily (2011a) spoke of up to 8.54 billion hectares being under some form of communal, collective control or legitimate claim (‘commons’). Alden Wily stressed that this, which represents 65% of terrestrial surface, includes most of the world’s forests (woodlands and mangroves), wetlands, and rangelands. Logically, the commons include most of the biodiversity and ‘conserved areas’ on our planet. If we reduce her estimate and take a very conservative value of only 6 billion hectares of commons existing on our planet and an even more conservative estimate that only half of that possesses an active local governance institution, we still obtain an estimate of 3 billion hectares (about one quart of planetary terrestrial surface) of territories of life or ‘conserved areas’ governed by their custodian indigenous peoples and local communities. Recently, Garnett et al. (2018) have confirmed these estimates. They noted that indigenous peoples alone have tenure rights over at least 3.8 billion hectares in 87 countries, intersecting with about 40% of all terrestrial protected areas and ecologically sound landscapes (for example, boreal and tropical primary forests, savannas and marshes). More analyses are needed but it is today impossible to doubt the significance of territories of life for both conservation of nature and human cultures, livelihoods and wellbeing.

Key references:

Alden Wily, 2011a; Jonas et al., 2014; Borrini-Feyerabend et al., 2014; Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill, 2015; Convention on Biological Diversity, 2018; Garnett et al., 2018; UNEP-WCMC, IUCN and NGS, 2018.

See also: Landmark; WRI page on indigenous and community land rights

[1] Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill, 2015, page 178.

[2] Convention on Biological Diversity, 2018b.

[3] In this way it was relatively easier to gather data, and the data reflected the power base of UN agencies: state governments. See UNEP-WCMC, IUCN and NGS, 2018.